Wisconsin Chamber Choir Reviews and News Articles

The Wisconsin Chamber Choir’s 20 year history is balanced with great a cappella choral singing and critically acclaimed performances with professional orchestral accompaniment. When the Wisconsin Chamber Choir performs a major work, it gains notice and acclaim. Here is what critics have to say about our performances:

The Wisconsin Chamber Choir’s 20 year history is balanced with great a cappella choral singing and critically acclaimed performances with professional orchestral accompaniment. When the Wisconsin Chamber Choir performs a major work, it gains notice and acclaim. Here is what critics have to say about our performances:

Click here to read “How Madison choirs safely harmonized during the pandemic“

April 21, 2015: John W. Barker finds the Wisconsin Chamber Choir moving and overwhelming in its performance of [the] “German” Requiem by Johannes Brahms. Note: John W. Barker (left) is an emeritus professor of Medieval history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He also is a well-known classical music critic who writes for Isthmus and the American Record Guide, and who for 12 years hosted an early music show every other Sunday morning on WORT FM 89.9 FM. He serves on the Board of Advisors for the Madison Early Music Festival and frequently gives pre-concert lectures in Madison.

Note: John W. Barker (left) is an emeritus professor of Medieval history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He also is a well-known classical music critic who writes for Isthmus and the American Record Guide, and who for 12 years hosted an early music show every other Sunday morning on WORT FM 89.9 FM. He serves on the Board of Advisors for the Madison Early Music Festival and frequently gives pre-concert lectures in Madison.

“Having already established an enviable level of achievement with his Wisconsin Chamber Choir (above), conductor Robert Gehrenbeck led it to new heights with the concert on Saturday night at Luther Memorial Church.

The program opened with two examples of Gehrenbeck’s interest in promoting new choral works through commissions.  The first, sung by the University of Wisconsin – Whitewater Chamber Singers at his academic base, was by American composer Christian Ellenwood [right].

The first, sung by the University of Wisconsin – Whitewater Chamber Singers at his academic base, was by American composer Christian Ellenwood [right].

Entitled “Prairie Spring,” it set a poem by Willa Cather, celebrating the Nebraska landscape, scored for choir and string orchestra. This is a gentle piece, full of lyric grace, in a neo-Romantic style, and reflecting a confident command of choral texture. It made me think a little of the music of British composer Gerald Finzi. The words were somewhat obscured, but that may

partly have been a function of the church’s spacious acoustics.

The second new work was by the older British composer Giles Swayne [left] that sets selected lines from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, under the title of “Our Orphan Souls.” Solo baritone Gregory Berg (below) delivered reflections of Captain Ahab, with chorus, alto saxophone, harp, double bass and percussion.

The second new work was by the older British composer Giles Swayne [left] that sets selected lines from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, under the title of “Our Orphan Souls.” Solo baritone Gregory Berg (below) delivered reflections of Captain Ahab, with chorus, alto saxophone, harp, double bass and percussion.

The solo writing has strength, and might have been built into a more extended soliloquy—and baritone Gregory Berg delivered it with strength. But the choral writing — sung by the Wisconsin Chamber Choir itself — was unsettled and unidiomatic, running from word to word without much continuity of lines.

Ah, but the main event! Nothing less than the “German” Requiem (Ein deutsches Requiem), one of the greatest of choral works, by one of the greatest of choral composers, Johannes Brahms (below). Setting passages from Scripture in the Martin Luther translation, Brahms made this a big work, both in length and in performing demands.

The chancel of Luther Memorial has only so much space, forcing a lot of crowding. The orchestra—37 players, familiar local performers—was arrayed through the center, while the two blended choirs were stationed on risers to either side: sopranos and tenors on the left, altos and basses on the right (right).

Such an arrangement could have strained ensemble coordination, but in fact it worked quite well. Indeed, it actually made it possible to follow the interaction of voice parts better than when the whole choir is in a single clump. German diction was a bit blurred, but, again, acoustics must take some blame. (I should note that I sat close and up front, so that what and how I heard may have been somewhat different from those in seating further back.)

The two soloists were both engaging. A last-minute replacement, soprano Catherine Henry, was deeply expressive, a rich-voiced exemplar of the comforting mother we would all want to have.

The baritone, Brian Leaper [right], was a deft guide to the mysteries of mortality.

The orchestra took on its large assignment with skill, and the choral singers were simply magnificent. But the highest praise must go to Gehrenbeck himself. His tempos were flexible, his balances neatly coordinated, and his sense of what each of the seven movements had to say was perfect. This is not only a superb choral conductor, but a musician of true artistry.

I write as someone for whom the Brahms Requiem has profound meaning. I have known and loved it since student days. I have sung in it several times, and listened to it in many recordings and performances. It is one of the musical threads of my life.

But I think I can honestly say that this was the most meaningful

performance of the work that I have ever experienced. I often felt moved to tears by the beautiful, truthful messages that Robert Gehrenbeck — who heads the choral program at UW-Whitewater — brought to realization out of it.

There is a small lifetime list I keep of concerts and performances that I forever cherish, and this one is a rare addition—a presentation I will remember for the rest of my days.

One more reminder, then, of the riches Madison offers in choral music alone.

The Mozart Requiem performed April 13, 2013 and reviewed by John W. Barker on April 15, 2013: The Wisconsin Chamber Choir unveils Robert Gehrenbeck’s own version of Mozart’s Requiem in a impressive concert that showed the links between Bach and Mozart.

Robert Gehrenbeck’s annual April concerts with his Wisconsin Chamber Choir have come to be important events on our musical scene, and his latest one, held at Luther Memorial Church on Saturday night, set new standards of enterprise.

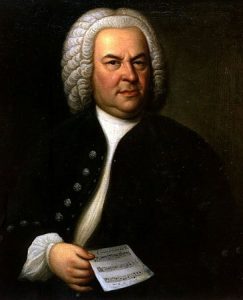

The essential point of the program was to observe the impact of music by Johann Sebastian Bach on Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s creativity, as illustrated  in works composed in the final months of the latter’s foreshortened life.

in works composed in the final months of the latter’s foreshortened life.

After a prologue of Mozart’s late motet, “Ave verum corpus,” we were given Bach’s glorious motet, “Jesu, meine Freude” to represent music that Mozart discovered among the works by the Leipzig master.

The first half ended with a march and the trial-by-fire scene from Act II of The Magic Flute. Then, after the intermission, came the pièce de résistance, Mozart’s great Requiem.

For the program’s first half, Gehrenbeck (right) limited himself to his own  group, the Madison-based Wisconsin Chamber Choir, which is 48 members strong.

group, the Madison-based Wisconsin Chamber Choir, which is 48 members strong.

Bach Scholars and musicians argue over how to treat this particular chorale-motet masterpiece — whether all of its 11 sections should be for full choir, or whether it should be done with a single singer per part, or whether some of its sections might be reserved for a consort of soloists.

While Gehrenbeck chose to give one section to a very tiny mini-chorus of eight singers, he opted otherwise for full five-part chorus throughout. Though the work comes to us as an a cappella piece, it is thought that instrument doublings were used by Bach (below).

Gehrenbeck avoided that approach, but he added a basso seguente, a doubling of the bass line by cello and organ, that was really not necessary musically, though it probably helped the singers on pitch.

Given the church’s acoustics, different parts of the very large sold-out audience received a varied choral sound, somewhat blended at the rear but still quite clear where I sat, up front, and given a beautiful glow in a careful but very satisfying performance

The March of the Priests and then the “Armed Men” scene, both from Mozart’s last opera, are full of spiritual and Masonic meaning. Here Gehrenbeck drew not only on some young solo singers, but also a small orchestra of 22 seasoned local players. While some parallels with Bach might be traced in these excerpts, the real influence for such material, not properly recognized, was Gluck (below). (Mozart never used trombones in his operas, save when he was drawing inspiration from Gluck’s techniques for solemn and ceremonial music.)

For the second half, devoted to the Requiem, Gehrenbeck added to the scene the 31 members of the Chamber Singers (below) of his home base, University of Wisconsin-Whitewater. He did, at least at one point, pare things down to his smaller local group, but otherwise he took the opportunity to create a very full and ample choral sound.Christoph Willibald von Gluck

To be sure, his tempos were judiciously cautious, designed so as not to push the pulses or strain the total bulk, but there was fine discipline throughout.

pulses or strain the total bulk, but there was fine discipline throughout.

The conductor produced some subtle nuances along the way. I particularly appreciated his clever pattern of decrescendo-to-crescendo on the repetitions of the words “quam olim Abrahae” in the Offertory.

Instead of having a single vocal quartet, Gehrenbeck used constantly changing groups of singers drawn mainly from the choir ranks. This gave rotating opportunities to lots of singers, some of them really good–I want to hear more of contralto Sarah Leuwerke–though at the price of constant parading of bodies on and off of the scene.

This performance had some very special qualities, however. An acknowledged and beloved masterpiece, Mozart’s Requiem nevertheless has textual problems that keep generation after generation of musicologists and editors in business. Mozart died before he could complete this last score, as is well known. His widow, desperate to have it finished to win the needed fee, first tried to have one Mozart student, Joseph Eybler, complete the work, but he soon pulled out, and her second choice was a lesser student, Franz Xaver Süssmayer, who carried out the task. (To the left is an etching of Sussmayer at Mozart’s death bed.)

Mozart died before he could complete this last score, as is well known. His widow, desperate to have it finished to win the needed fee, first tried to have one Mozart student, Joseph Eybler, complete the work, but he soon pulled out, and her second choice was a lesser student, Franz Xaver Süssmayer, who carried out the task. (To the left is an etching of Sussmayer at Mozart’s death bed.)

Süssmayer’s version of the score long stood as its “standard” performing version, but in recent decades editors have been seeking ways to overcome its weaknesses and get closer to what Mozart himself would have done.

Thus, Franz Beyer has cleaned up the orchestration, and has added notes to the end of the “Hosanna” refrains to the Sanctus and Benedictus which bring Süssmayer’s abrupt conclusions more into line with Mozartean style. Other editors have gone much further into rewriting what are understood to be just Süssmayer’s own contributions.

Robert Gehrenbeck conducting has now entered these lists on his own merits. He has basically used the Beyer edition, but replaced the wind and timpani parts in the Dies irae with those that Eybler had originally proposed. Gehrenbeck has also interpolated a short passage in the Benedictus to allow for an appropriate change of key.

In all these respects, Gehrenbeck’s educated guesses are as good as anybody else’s. In this uniquely personal collation, he has created a fully plausible text for a fully convincing performance.

What a refreshing, thought-provoking, and inspiring concert! Remember, Madisonians, how lucky we are.

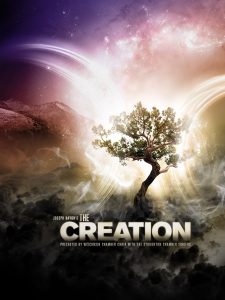

Joseph Haydn’s Creation was performed on April 2, 2011. It received a great deal of attention from Madison critics, Jay Rath, Jake Stockinger, and John W. Barker. Here are their reviews:

Jay Rath wrote on April 3, 2011: Haydn’s greatest “Creation” thrills

Joseph Haydn’s self-proclaimed masterpiece, The Creation, met with an instant and enthusiastic standing ovation in Madison on Saturday evening. Around 440 attended the performance by the Wisconsin Chamber Choir and Stoughton Chamber Singers at the Madison Masonic Center. The Creation is properly termed an oratorio, but in many ways it resembles an opera staged concert-style, complete with characters Adam, Eve and three angels. As we head into the Easter season it would be a fine salute to this year’s 400th anniversary of the King James Bible, from which the text is drawn (along with Milton’s Paradise Lost). Or it would be, except the English libretto was translated into German for Haydn, and then translated back into English several times. The work tells the story of Biblical creation and the early days of Eden, foreshadowing the fall from grace. The performance overall was rich, lush and satisfying, presenting great caramel-flavored swirls of sound. The choir was always precise in phrasing, and stunning in its presentation of big, wide-open chords.

The work tells the story of Biblical creation and the early days of Eden, foreshadowing the fall from grace. The performance overall was rich, lush and satisfying, presenting great caramel-flavored swirls of sound. The choir was always precise in phrasing, and stunning in its presentation of big, wide-open chords.

Soprano Deanna Horjus-Lang was bold and athletic; bass Brian Leeper presented a fine anchor throughout. Madeline Olson, as Eve, performed with bright ease. J. Adam Shelton was a stand-out as the angel Uriel, with his fine, clear tenor.

Many of the soloists were drawn from the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, as was conductor Robert Gehrenbeck, who led the choirs and fine orchestra in a spare, effective manner.

The auditorium of the Masonic Center revealed itself as an excellent space for live classical presentation, with little or no amplification evident or even necessary. The center is too seldom-used, despite its history as a home for the Wisconsin Chamber Orchestra’s annual presentation of Handel’s Messiah in the 1980s.

Let’s hope for many more concerts there from the outstanding Wisconsin Chamber Choir and Stoughton Chamber Singers. The concert was made possible in part by support from the Dane County Cultural Affairs Commission and the Overture Foundation.

Jake Stockinger wrote on April 5, 2011 in “The Well-Tempered Ear:”

By one local critic’s count, Haydn’s “The Creation” has been performed only three times in the past 35 years or so in Madison.

That is too bad for one of the all-time great masterpieces of oratorio writing. But at least, it seems, when it performed it is generally performed well. Certainly such was the case with last Saturday’s outstanding performance of “The Creation” by the 45-member Wisconsin Chamber Choir and the 18-member Stoughton Chamber Singers with soloists and a 31-piece pick-up orchestra form local groups.

These are not high-profile groups in a city filled with so many fine classical music ensembles. But perhaps this kind of performance could bring them a bit more publicity and profile. It certainly should. As Isthmus critic and retired UW history professor John W. Barker pointed out during his crowded pre-concert lecture, Haydn’s oratorio was the prolific composer’s single most worked by the great composer of 104 symphonies. And it stands squarely in the middle of the oratorio tradition, looking backward to Handel and forward to Mendelssohn and others.

These are not high-profile groups in a city filled with so many fine classical music ensembles. But perhaps this kind of performance could bring them a bit more publicity and profile. It certainly should. As Isthmus critic and retired UW history professor John W. Barker pointed out during his crowded pre-concert lecture, Haydn’s oratorio was the prolific composer’s single most worked by the great composer of 104 symphonies. And it stands squarely in the middle of the oratorio tradition, looking backward to Handel and forward to Mendelssohn and others.

Everything about the performance, which just got better and better as the singers and instrumentalists progressed and warmed up, seemed appropriate.

Even the venue fitted the piece. It was performed in the Masonic auditorium (below), on Wisconsin Avenue, near the Capitol, and Haydn was a Mason in Vienna for two years. The concert hall itself seems an intimate space with good acoustics, and one wishes it were used more often.

True, the performance was not sold-out. But it was a very good size crowd and an enthusiastic one. I found the instrumentalists particularly good at the many moments of sound painting used in the score: the bright voices bringing light to chaos; the strings portraying the first dawn of the first day; the flute-made bird calls; the trombone hoof beats of galloping animals; and the double-bass lumbering of great whales.

All sections performed well, but I was particularly struck by the brass (hard instruments to play), the winds and by the constant but never flagging fortepiano continuo provided by Theodore Reinke. At times the orchestra seemed a bit loud for the chorus, but the balance improved as the performance progressed.

But of course, it was the vocalists – soloists and choirs alike – who rightfully reigned over this creation of “The Creation.”

Some standouts included soprano Deanna Horjus-Lang as the angel Gabriel, who voice often soared effortlessly. Both tenor J. Adam Shelton as Uriel and bass Brian Leeper (below, second from left) as Raphael proved excellent narrators, whose excellent diction allowed us to hear the English text and who sang with both lyricism and an assertive seriousness.

As the newly created Adam and Eve, bass Michael Roemer and soprano Madeline Olson somehow embodied innocence through their young and lighter voices. The seemed perfected matched to my ears.

All of this is a great compliment to Robert Gehrenbeck, the Wisconsin Chamber Choir’s artistic director since 2008, who held the performance together with the appropriate tightness that deserved the standing ovation it got.

All of this is a great compliment to Robert Gehrenbeck, the Wisconsin Chamber Choir’s artistic director since 2008, who held the performance together with the appropriate tightness that deserved the standing ovation it got.

If the work itself seemed less expressive than one might imagine, well that is one of the great contrasts between Haydn and the emotionally deeper Mozart, to whom he is so often – and so unjustly — compared. The underlying belief was the religion of Reason and the Enlightenment, not the profundity of a personal statement, even though Haydn was a devout a Roman Catholic.

In any case, Haydn (below) considered “The Creation” his best work. And to sing it with comparable conviction is not an easy task. But it is one that was fulfilled by this performance, which brought a lot of light of its own to this often-neglected masterwork and to a dark time.

Review by John W. Barker for Isthmus on April 2, 2011: Wisconsin Chamber Choir’s performance of Haydn’s Creation a resounding success!

Haydn’s oratorio The Creation is a glorious, exhilarating work, one of the triumphs of the choral literature. I can think of at least two earlier performances in Madison in my time, as done by the Madison Symphony Orchestra and its chorus. One was in 2002 under John DeMain. The prior one was in the spring of 1974. Led by Roland Johnson, it had special meaning for me. I sang (joyously) in the chorus for it, and then, a few weeks later, I was in Vienna and visited Haydn’s house, now a museum — the very house where Haydn composed this wonderful music. It was still in my ears, and it vibrated through the place for me as I walked its rooms. Unforgettable!

So I looked forward with high expectations to the April 2 performance of The Creation by the Wisconsin Chamber Choir. And I was not disappointed. (Disclosure: I gave a pre-concert lecture.) The setting itself, the Masonic Center auditorium, was meaningful to begin with, for Haydn himself was briefly a Freemason in Vienna, and Masonic imagery and ideas peek out as a subtext in this and others of his works. (Over the center’s entrance reads the Masonic motto: “Let there be Light”, words that Haydn actually set in his score, with dazzling effect.)

Fortunately, too, the music-making was simply splendid. Having brought off Bach’s St. John Passion last season, conductor Robert Gehrenbeck once more showed bold enterprise in tackling this new and major project. With great directorial skill and with thorough understanding of the music, he brought it off triumphantly. His choir of 42 singers was augmented with 18 members of the Stoughton Chamber Singers, all singing (in English) with lusty sonority. A chamber orchestra of 31 players was made up of local instrumentalists: there were a few blemishes in tricky passages, but the playing was remarkably crisp and compelling, with some particularly beautiful wind work. That these players and Gehrenbeck could manage this with only two orchestral rehearsals is a great tribute to the professionalism involved.

For the solo assignments, there were five singers in all. Of those who portrayed the three archangels in Parts I and II, tenor J. Adam Shelton (Uriel) and bass Brian Leeper (Raphael) sang their parts with strength and style, but soprano Deanna Horjus-Lang (Gabriel) brought a special beauty to her work, soaring over everyone else with radiant clarity. For Part III we were given two new soloists, Madeline Olsen (a member of the choir) as Eve and bass Michael Roemer as Adam. Their glowingly beautiful, fresh young voices captured perfectly the charming innocence of the Primal Pair.

Solos and choruses, tumbled forth one after the other, each with new melodic beauties, nature evocations, and rich majesty, to express the beauties of our world and the optimism of faith. At a time now so full of anger, ugliness, and hostilities, we need all the uplift we can get. Thanks to Gehrenbeck and Haydn, that was what we came away with in grateful abundance.

Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. John Passion was performed on April 3, 2010 and was reviewed by John Barker: St. John Passion – A Resounding Success: Review in Isthmus Daily Page St. John Passion Wisconsin Chamber Choir performs superbly disciplined ‘St. John Passion’

Wisconsin Chamber Choir performs superbly disciplined ‘St. John Passion’

Artistic director Robert Gehrenbeck pulled together a remarkably consistent, coherent, and artistically splendid achievement. Are we developing an historic, and “historically informed” tradition each Easter now?

Last year, Trevor Stephenson’s Madison Bach Musicians, et al., gave us the first period-style performance ever here of Bach’s monumental “St. Matthew Passion”. Now, this year, Robert Gehrenbeck, leading his Wisconsin Chamber Choir, has given us Madison’s first period-style presentation of Bach’s “St. John Passion”. Shorter, more concise and intense that the “Matthew Passion”, the “John” setting has a complex history of recurrent revisions by the composer through his Leipzig career. Perhaps never finished to his satisfaction, it comes  down to us nevertheless as a compelling Christian drama. Gehrenbeck’s choir numbered 32 mixed voices — perhaps a tad larger than Bach might have used, but superbly disciplined, of beautifully balanced sonority, and with notably clear German diction. A group of 17 period-instrument players contributed a pungent accompaniment that a modern orchestra could not have matched, with fine obbligato work by individual members, and ever-solid continuo foundation provided by cellist Anton Ten Wolde and organist John Chappell Stowe. It was a pity, though, that a lutenist could not have been mustered for the curious lute obbligato part in the bass arioso “Betrachte, meine Seel”. In any Passion performance, the narrative role of the Evangelist is pivotal, and clear-voiced James Doing (who also took one of the tenor arias) has this music in his blood.

down to us nevertheless as a compelling Christian drama. Gehrenbeck’s choir numbered 32 mixed voices — perhaps a tad larger than Bach might have used, but superbly disciplined, of beautifully balanced sonority, and with notably clear German diction. A group of 17 period-instrument players contributed a pungent accompaniment that a modern orchestra could not have matched, with fine obbligato work by individual members, and ever-solid continuo foundation provided by cellist Anton Ten Wolde and organist John Chappell Stowe. It was a pity, though, that a lutenist could not have been mustered for the curious lute obbligato part in the bass arioso “Betrachte, meine Seel”. In any Passion performance, the narrative role of the Evangelist is pivotal, and clear-voiced James Doing (who also took one of the tenor arias) has this music in his blood.

Likewise a veteran of this idiom is Paul Rowe, who sang the words of Christ. The four soloists in the arias were all admirable: I particularly liked the familiar tenor Ryan McEldowney, and contralto Julie Cross was quite moving in the great aria, “Es ist vollbracht!” Of the three members of the choir who took the small “character” roles, I was most impressed by baritone’s William Rosholt’s  vivid and vocally rich portrayal of Pilate.

vivid and vocally rich portrayal of Pilate.

The performance was given, like last year’s “Matthew Passion” in the new Atrium Auditorium of the First Unitarian Society. Considerable support effort was in evidence. The handsomely produced printed program was remarkably thorough and detailed, with full text and translation. As a backup to that, large-print supertitles were projected on a side screen, to encourage close following of the text. Ventures like these can be a down-to-the-wire scramble, but Gehrenbeck managed to pull together a remarkably consistent, coherent,

and artistically splendid achievement. He and his choir should be proud of establishing for themselves a more glowing status than ever in Madison’s musical life.

And, like the two performances of the “Matthew Passion”, the one presentation this time was sold out, with people turned away. Clearly, Madison audiences have come to welcome period-style recreations of literature once held captive to “modern” treatments. Food for thought here.